11 Απρ Πως το λαγουδάκι έγινε σύμβολο του Πάσχα;

Matthew Wilson finds out.

Coming up with an answer is not as easy as it may appear – the hunt will take us down a few rabbit holes, not unlike Alice on her voyage through Wonderland. Three rabbity themes cut across global mythology and religion: bunnies’ perceived sacredness, their mystical link to the moon, and their connection with fertility. The chase will incorporate both rabbits and hares – when examining folklore and art history, it is sometimes hard to distinguish between the two. They are both part of the taxonomic order Lagomorpha, and the family Leporidae, and have often been treated in the same way in religions, fables, and in visual culture.

Are rabbits connected with Easter because they’ve often been considered holy? Hares were venerated in Celtic mythology, and are portrayed as canny tricksters in the myths of Native American tribes including the Michabo and Manabush. Similar tales are to be found in Central African fables and the related figure of Br’er Rabbit, the ultimate hero of cunning. It’s impossible not to see cartoon rabbits – including Bugs Bunny – also following in this ancient tradition of the animal’s craftiness. According to folklore in the United Kingdom, witches can transform into rabbits and hares, and in many cultures they are seen as harbingers of both good and bad luck. Hares are fast and agile runners, which may account for the general perception of them as either wily, or mysterious and obscure.

The ‘three hares’ symbol has been found across the world, and from more than 1300 years ago (Credit: Alamy)

Backing up this view is the fascinatingly transnational phenomenon of the “three hare” symbol. It depicts three hares running in a never-ending circle with their ears touching to form a triangle. You can find it being used in many medieval churches in the UK – in South Tawton (Devon), Long Melford (Suffolk), Cotehele (Cornwall), St David’s Cathedral in Pembrokeshire, and Chester Cathedral. Long considered a native icon to British scholars, it was subsequently discovered across Europe, in cathedrals and synagogues in Germany, in French parish churches – but also on artefacts created in Syria, Egypt and the Swat Valley in Pakistan dating back as far as the 9th Century AD.

The earliest example can be found in the Dunhuang Caves in China, a Buddhist holy site created in 6th Century AD. The appeal of the “three hares” symbol is partly in its central optical illusion – individually each hare has two ears, but it looks like there are three in total. The reason it was dispersed so widely is probably due to international trade in the first millennium AD. Along with many other pervasive artistic symbols, it likely featured on objects that were bought, sold, and exported along the Silk Roads that linked Europe with Asia. It is believed that the symbol implies prosperity and regeneration through its cyclical composition and overlapping forms. The themes of renewal and rebirth seem linked to the Easter message. Could the Easter Bunny have derived from this ancient Buddhist symbol?

The “three hare” symbol is believed to have originated in a story in the Jatakas (tales concerning the lives of Buddha) about the “hare of selflessness”. In this story the hare is a previous incarnation of the historical Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama. He is so generous and devout that when he meets a starving priest, he self-sacrificially clambered into a fire to provide him with a meal. As a reward for his virtue, the hare’s image was cast on the moon. This story, and hares’ lunar associations in general, probably derived from much more ancient religions in India. The moon does indeed have a marking on its surface which looks (with a little imagination and squinting) like a hare.

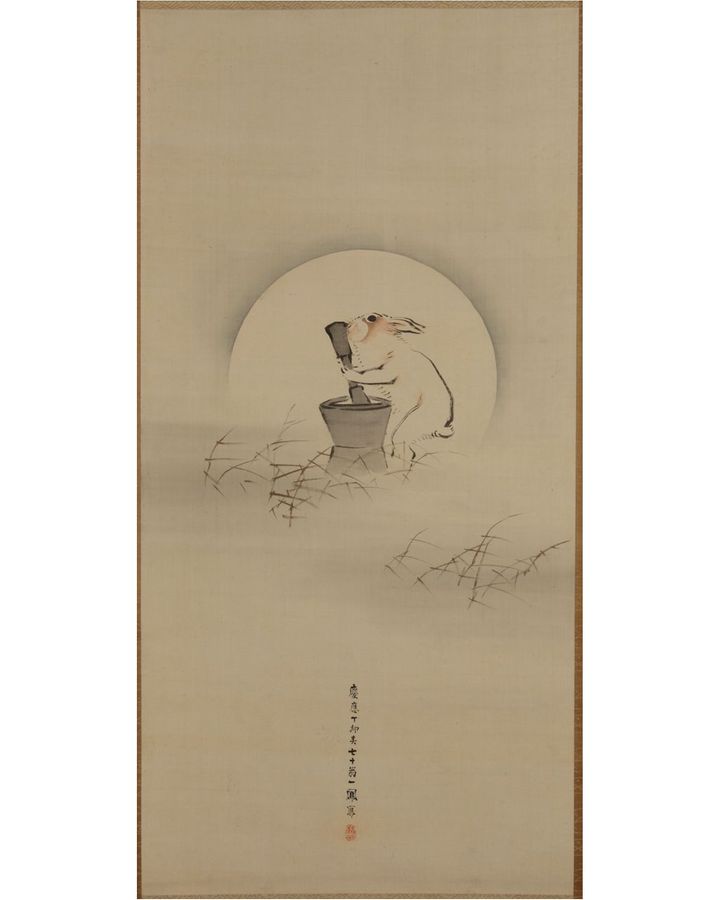

A mystical hare inhabits the moon in Japanese folklore, as shown in Rabbit Pounding the Elixir of Life Under the Moon by Mori Ippo, 1867 (Credit: New Orleans Museum of Art)

Moon-inhabiting and moon-staring hares proliferate across the visual cultures of China, Japan, and Korea. Taoist traditions in China relate a story about a moon-dwelling rabbit who pounds together the ingredients of the elixir of life. Indigenous North and Central American culture have very similar myths that connect hares and rabbits with the moon, presumably because they also detected lagomorphic markings on the lunar surface. It seems that the rabbit is an honoured creature, synonymous with celestial powers and rejuvenation not just for Christians at Easter, but across the world.

Bunnies and fertility

Even though symbolism and animal fables from the East have entered European iconography, the origins of the Easter Bunny might lie closer to home. Most Christian symbols derive from Biblical sources, although some survived from the art cultures of ancient Greece and Rome.

The Bible offers mixed attitudes towards rabbits. In the books of Deuteronomy and Leviticus, they are referred to as impure animals. However, in Psalms and Proverbs they are described as possessing some intelligence, although ultimately condemned as weak.

What fascinated ancient Greek and Roman writers most about our leporine friends was their fertility. The philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BC), for example, noted how rabbits could breed at jaw-dropping speed. Another influential writer, Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD), mistakenly believed that their breakneck procreation was due to the fact that hares were hermaphrodites, and that childbirth was shared by both males and females. Could the Easter Bunny be connected to this classical idea of fertility, used to express the rejuvenation and fecundity of springtime?

In the medieval and Renaissance periods, rabbits could either be symbols of chastity or boundless sexuality, depending on the context

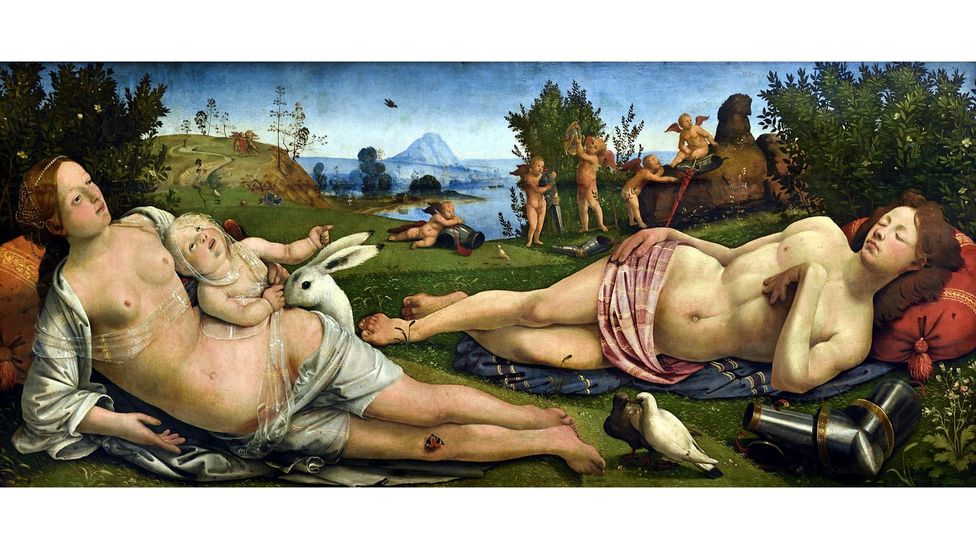

Such astonishing skills in biological reproduction certainly had an impact on European symbolism. In medieval and Renaissance art, rabbits were frequently represented alongside Venus, the ancient Roman goddess of love and sexuality. Lust is one of the seven deadly sins, and when artists depicted it in allegorical form (“Luxuria”), it sometimes took the form of a woman with a bunny.

Rabbits have sometimes been a symbol for lust, as in Venus, Mars, and Cupid (1490) by Piero di Cosimo (Credit: Alamy)

The Roman author Aelian (c175-c235 AD) suggested that hares were capable of superfetation – the ability to gestate an embryo whilst already pregnant. For a long time, this was scoffed at, but recent science has proved that hares are indeed capable of such a feat. Aelian and other observers of this phenomenon believed that hares and rabbits could give birth without copulation. So, weirdly, in the medieval and Renaissance periods, rabbits could either be symbols of chastity or boundless sexuality, depending on the context.

In The Madonna of the Rabbit (1520-30) by Titian, a bunny symbolises chastity (Credit: Getty Images)

This can be seen when we compare Titian’s serene and luminous The Madonna of the Rabbit (1520-30) with Pisanello’s bewitching Allegory of Luxuria (1426). In Titian’s painting, the pure white bunny is a symbol of Mary’s celibacy. In Pisanello’s drawing, the rabbit symbolises lechery.

Whereas in Pisanello’s Allegory of Luxuria (1426), a rabbit takes on a completely different meaning (Credit: Alamy)

These biological traits of rabbits and hares also prompted association with fertility in otherwise disconnected cultures. In Aztec mythology, there was a belief in the Centzon Tōtōchtin – a group of 400 godly rabbits who were said to hold drunken parties in celebration of abundance.

Even within Europe, different societies used rabbits as an icon of fecundity and linked them to deities of reproduction. According to the writings of the Venerable Bede (673-735 AD), an Anglo-Saxon deity named Ēostre was accompanied by a rabbit because she represented the rejuvenation and fertility of springtime. Her festival celebrations occurred in April, and it is commonly believed that through Ēostre we have acquired the name for Easter as well as her rabbit sidekick. If this is right, it means that long ago, Christian iconography appropriated and adopted symbols from older, pagan religions, blending them in with its own.

Does this close the case on the origins of the Easter Bunny? The problem with trying to give any definitive answer is the lack of evidence. Apart from Bede, there is no clear link between Ēostre and Easter, and Bede can’t be considered a direct source on Anglo-Saxon religion because he was writing from a Christian perspective. While it might seem very likely, the connection can never be proved for certain.

Rather like in Alice in Wonderland, the white rabbit can never be fully grasped. Through history, rabbits and hares have been seen as sacred and the epitome of craftiness. They have been connected with the enigmatic purity of the moon, with chastity and with superlative powers of fertility. It is with some justness that this supremely enigmatic animal continues to evade meaning. The further we chase the origins of the Easter Bunny, the more he disappears down the dark warrens, teasing our desperation for a logical answer to a surprisingly complex puzzle.

(πηγή: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20230403-the-easter-bunny-evolution-of-a-symbol)